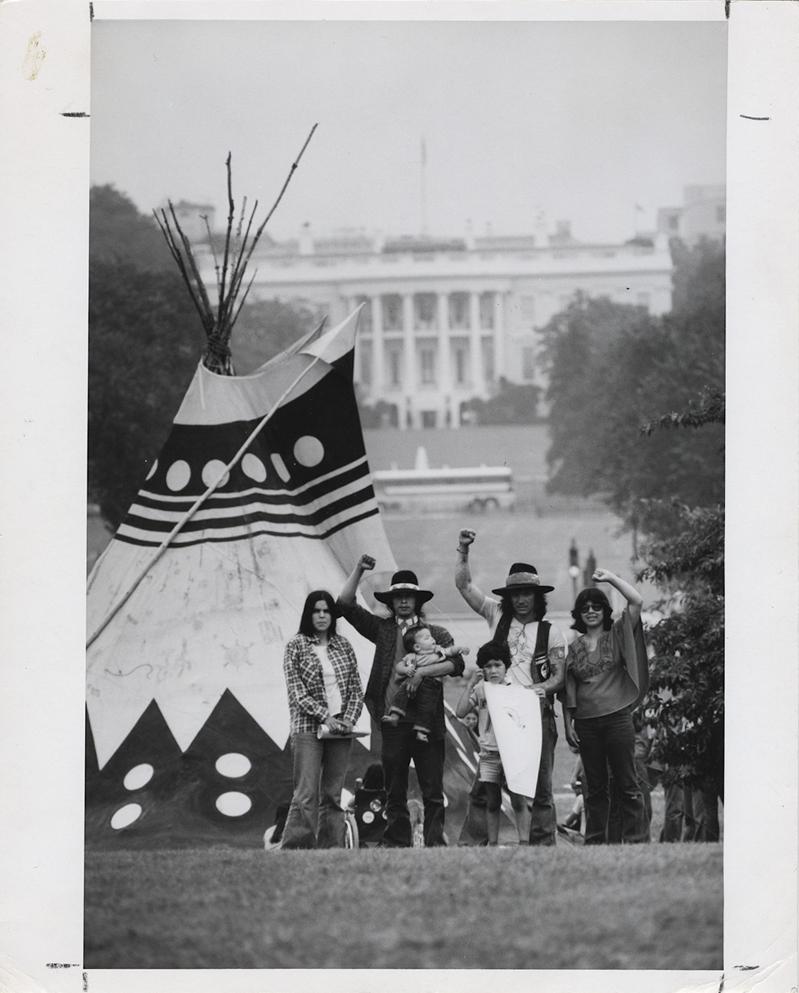

Frank B. Johnston, Indians Demonstration, Washington DC, USA, gelatin silver print, July 1978. Reproduction from the Black Star Collection at Ryerson University. Courtesy of the Ryerson Image Centre.

GHOST DANCE Activism. Resistance. Art. at the intersection of events and artistic practice, Aboriginal artists manifest an aesthetic of resistance

May. 27, 2013

Ghost Dance: Activism. Resistance. Art. combines commissioned works, existing works and photographs from the Black Star Collection to examine the role of the artist as activist, as chronicler and as provocateur in the ongoing struggle for Indigenous rights, self determination and sovereignty. The exhibition, curated by Steven Loft, will be on view September 18 - December 15, 2013 in the Ryerson Image Centre’s Main Gallery, University Gallery, and on the Salah J. Bachir New Media Wall.

Artists include Sonny Assu, Vernon Ah Kee, Scott Benesiinaabandan, Dana Claxton, Cheryl L'Hirondelle, Alan Michelson, Theo Sims, Skawennati, and Jackson 2bears. The public opening reception for Ghost Dance: Activism. Resistance. Art. will take place Wednesday, September 18, 2013, 6-8pm.

Three key events are used as conceptual starting points to examine Indigenous activism through the works of Aboriginal artists:

Jack Wilson (or Wovoka), a young Paiute man, had a vision during an eclipse of the sun in 1889, of a place where his ancestors were once again engaged in their favourite pastimes, where wild game and abundant food were restored to the lands. He interpreted the vision as the coming of a new age, one where Native and non-Native people would finally live in peace. This was the birth of the Ghost Dance — quite possibly the first pan-Indian movement in the United States.

In the autumn of 1969, thousands of American Indians occupied the abandoned remains

of Alcatraz, the federal penitentiary that housed America's most notorious criminals until closing in 1963. The occupiers held the island for nearly eighteen months, from November 1969 until June 1971, reclaiming it as Indian land and demanding fairness and respect for Indian peoples. U.S. policy toward Indians had worsened, despite repeated pleas from American Indian leaders to honor treaties and tribal sovereignty. The occupation of Alcatraz was about human rights, the occupiers said.

A peaceful vigil by the Mohawk citizens of Kanesatake who were protesting against a plan by the municipality of Oka to enlarge a golf course on their ancestral territory took a drastic turn on July 11, 1990, when the Quebec provincial police attacked the protesters, leading to a 78--" day standoff between Mohawks, the Quebec police, and ultimately, the Canadian military.

Steven Loft, the exhibition’s curator, explains, “Indigenous art is not predicated on colonialism, but on the events caused by it. At first glance it would seem counter--"intuitive. Colonialism has been the cause of the suffering, oppression and violence perpetuated against Aboriginal people in this and many other countries, for centuries. But attributing the rise of resistance, activism and the art associated with it to colonialism itself, is disingenuous. Societies, and the people in them, are changed by events. It is the interactions of people which manifest the destructive ideologies inherent in colonialism. By concentrating on events, we humanize the process, allowing a more nuanced and human response. We can see it was people who committed atrocities against others, not the ideology behind it. And we can see the presence of real people that stand up and resist it.”

The work of Indigenous artists needs to be understood through the clarifying lens of sovereignty and self-determination, not just in terms of assimilation, colonization and identity politics [...] Sovereignty is the border that shifts Indigenous experience from victimized stance to a strategic one.[2]

Steven Loft is Scholar-in-Residence at the Ryerson Image Centre and the National Visiting Trudeau Fellow at Ryerson University. He is a curator, theorist, writer, and media artist. Steven Loft came to Ryerson University after completing a two year residency as the first Aboriginal curator"in"residence at the National Gallery of Canada. From 2002 to 2008, he was the Director of the Urban Shaman Gallery (Winnipeg), Canada’s largest aboriginal artist-run centre. Prior to that, Mr. Loft was First Nations Curator at the Art Gallery of Hamilton and Artistic Director of the Native Indian/Inuit Photographers’ Association. He has curated gallery exhibitions, programmed media arts festivals, created video works, and written about aboriginal art and aesthetics for magazines, catalogues and arts publications.

Ghost Dance: Activism. Resistance. Art. is made possible through the generous support of the Trudeau Foundation, Ryerson University, the Ontario Arts Council, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Toronto Arts Council and The Paul J. Ruhnke Memorial Fund.

The exhibition has been financially assisted by the Ontario Cultural Attractions Fund, a program of the Government of Ontario through the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport, administered by the Ontario Cultural Attractions Fund Corporation.